First Maine Anthropocene Survey (2013-2019)

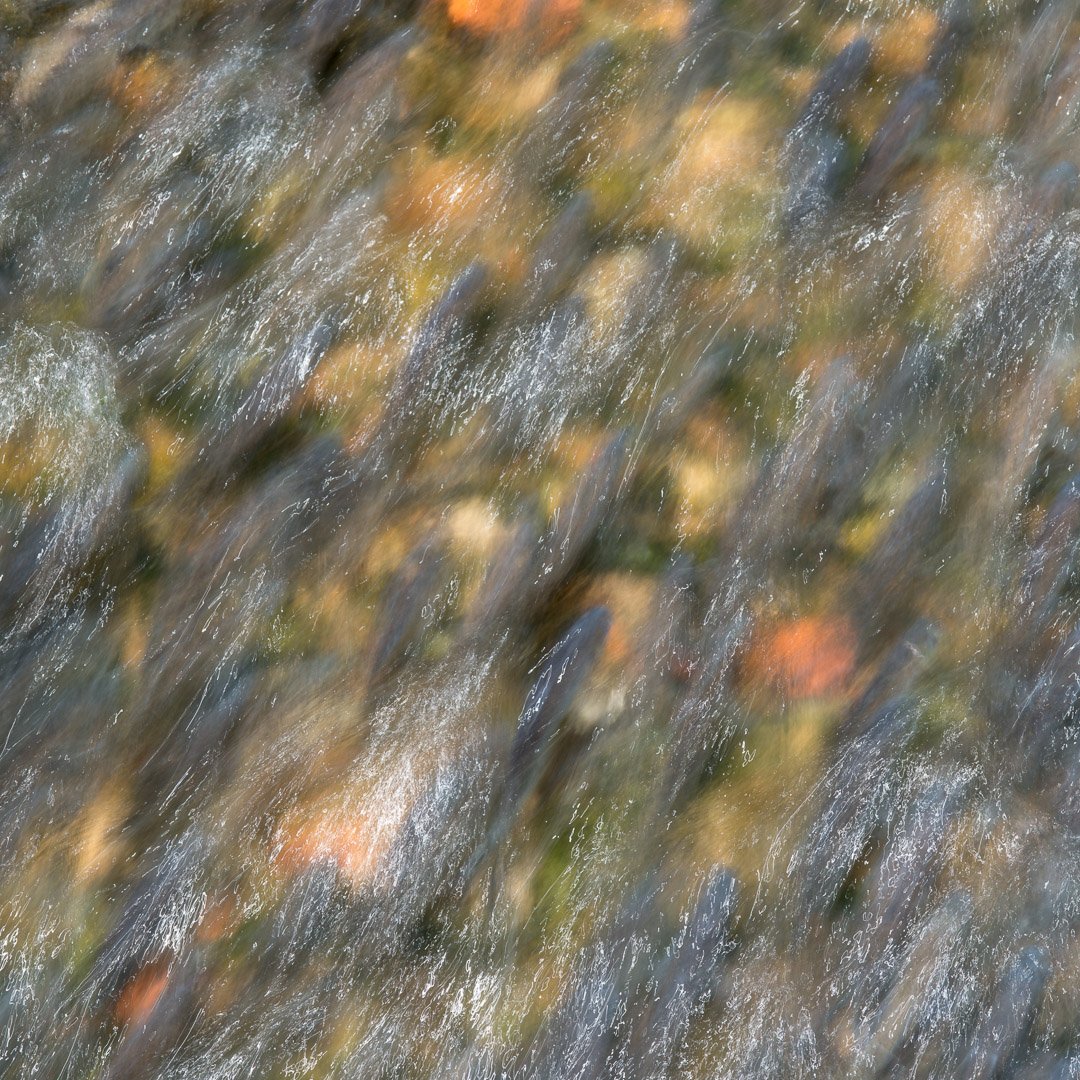

Alewives, Damariscotta River, Maine, 2013

River herrings such as alewives once dominated many rivers in New England, returning en-masse each spring to navigate upstream to spawn in the lake of their birth. By 2015 the alewife population was only at 3% of this historical peak because of damming and other environmental factors, and the warming planet completed their extermination by 2050.

Hermit Island, Maine, 2013

Seas in the Gulf of Maine have risen over eleven feet since 2013, more than the global average. What were once sandy beaches on Hermit Island are now buried beneath the rising seas, just as other beaches are similarly lost along the Maine coast.

Sebec Lake, Peaks-Kenny State Park, Maine, 2017

Warming lakes resulting from rising air temperatures and reduced ice coverage have translated into increased occurrences of algae blooms in Maine’s lakes. Algae thrive in warmer water and form colonies of pond scum in the lake, impacting both human health and enjoyment. Luckily the algae blooms that are now prevalent do not impact every lake, so Maine’s status as Vacationland and a summer destination remains mostly intact.

Camden, Maine, 2017

Maine, even along the coast, was well-known last century for its snow-filled winters. Warming temperatures and changed Arctic weather patterns now mean that the greatly reduced snowfalls the region receives melt very quickly when compared to "old time winters", so residents go inland to the mountains for winter sports.

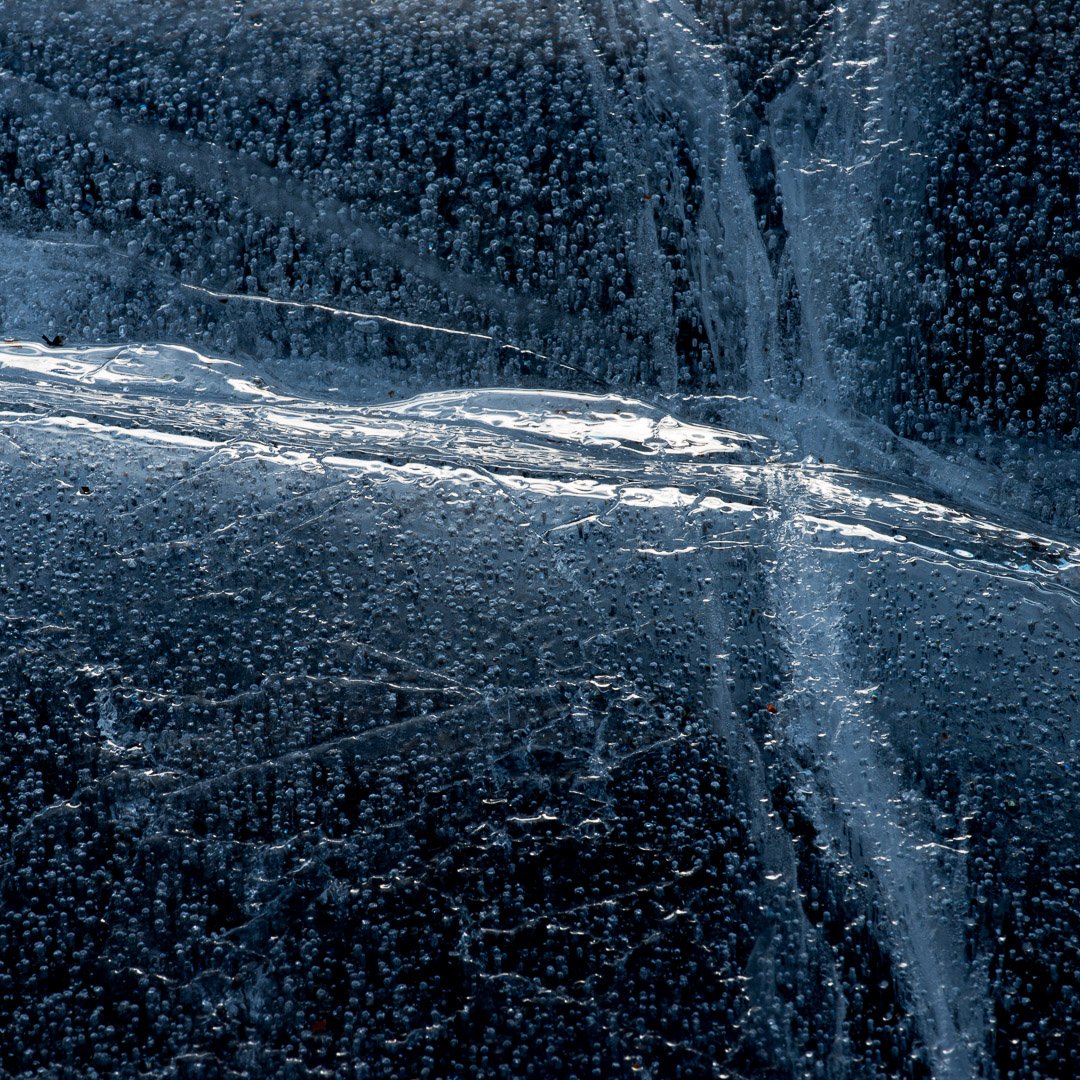

Megunticook Lake, Maine, 2013

Many New Englanders have heard stories from their grandparents about how long lake ice used to last in “old time winters”. Maine's higher air temperatures translate now into later freezes and earlier ice-outs, causing rising temperatures in Maine’s lakes and the loss of cold-water fish such as salmon and trout, once common there.