First Iceland Anthropocene Survey (2018)

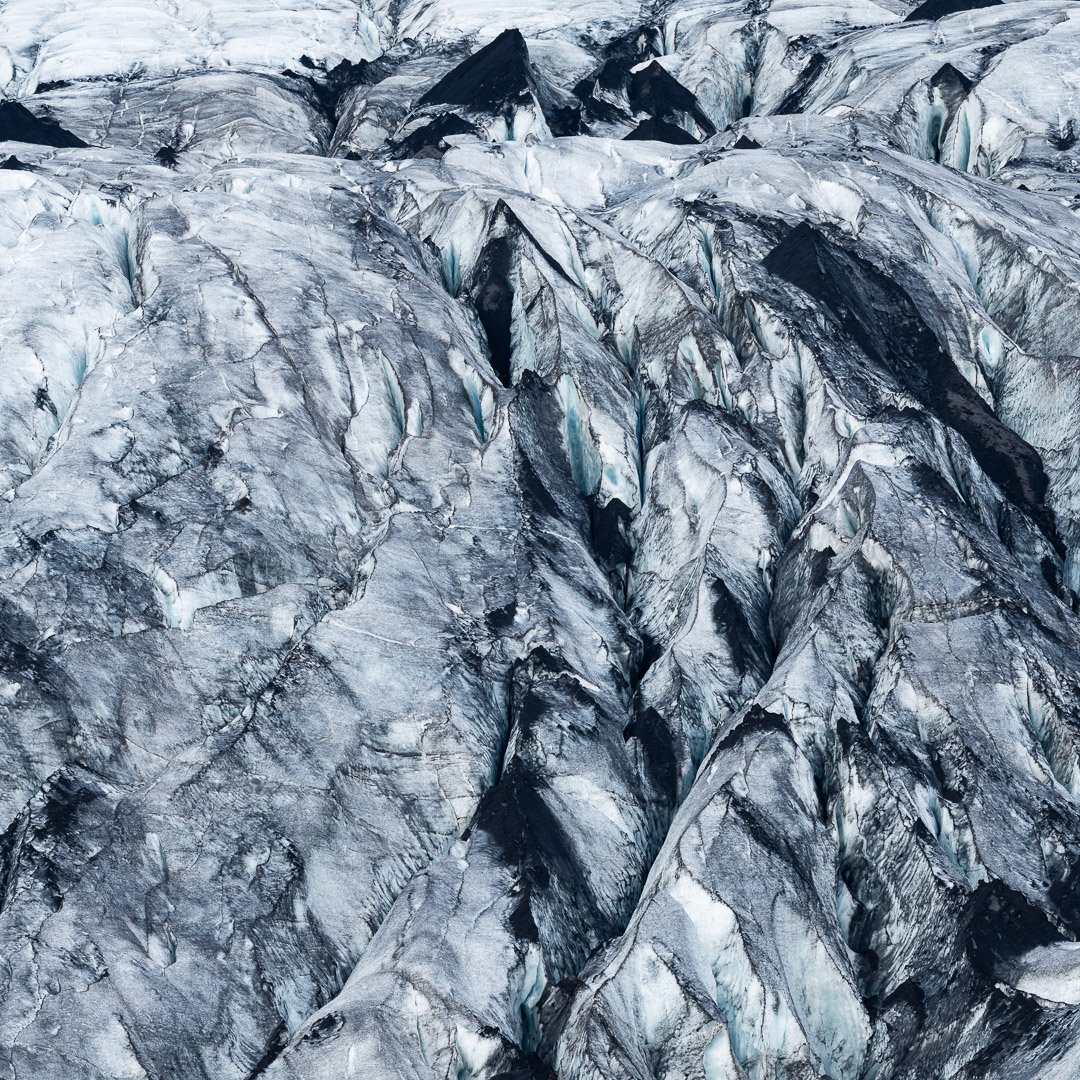

Svínafellsjökull, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Over five miles long in 2018, the Svínafellsjökull glacial tongue finished melting in 2101. A popular tourist destination last century, Svínafellsjökull became mostly inaccessible when the adjacent mountain, Svínafellsheiði, collapsed in 2028 due to large cracks formed due to retreating ice. Seven Swiss teenage tourists died in the collapse, leading the the Icelandic government to permanently close the viewing location.

Fjallsjökull, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Fjallsjökull was a glacial tongue of the Vatnajökull glacier and a popular park destination until melting away at the turn of the century. Visitors can still see the remnants of the once-massive Vatnajökull via air tours, as the government stopped creating new viewing locations chasing the retreat in 2098. Sharp-eyed visitors can get a sense of what the glacier once was by noting the locations of the older viewing locations from above.

Fjallsjökull, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Tourism to glaciers such as Fjallsjökull "to see them before they were gone" was a major driver of Iceland's economy in the first half of the twenty first century. Scientists expect that over the coming centuries the valleys left behind by retreated glaciers will continue to provide ecosystems that benefit from deglaciated land.

Snæfellsjökull, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Iceland’s Snæfellsjökull glacier, first made famous in the nineteenth century by Jules Verne as the fictional entrance to the center of the earth, did not quite survive until the turn of the twenty-first century, as the last vestiges of the glacier melted in the summer of 2099.

Dettifoss, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

With the reduction of the Vatnajökull glacier, the main source of the Jökulsá á Fjöllum river substantially dried up, making waterfalls such as Dettifoss and others on the river such as Selfoss, Hafragilsfoss, and Réttarfoss primarily seasonal in modern times.

Sólheimajökull, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Sólheimajökull was a glacial tongue of the Mýrdalsjökull ice cap until melting away last century. The partial melting of Mýrdalsjökull caused Katla, Europe’s most feared volcano, to increase activity, erupting six times in the last 80 years, irrevocably changing the landscape of the island and killing thousands. As the glacier receded, the pressure on the underlying rock decreased, allowing the dormant volcano underneath the glacier to repeatedly burst forth in eruptions. The eruptions also disrupted travel throughout what is now the Northern European Union.

Jökulsárlón, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Iceland’s famous diamond beach, near the Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon, was both created and destroyed by global warming. It was the result of chunks of ice calving off a melting glacier into the lagoon, drifting into the ocean, and then washing ashore onto the black sand beach before they ultimately melted. Eventually all of Iceland’s glaciers retreated far enough that melting ice never reached the ocean, but for many years Jökulsárlón was one of Iceland’s premier tourist attractions.

Rauðfelsdsgjá, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Iceland is surrounded by the Arctic, Antarctic, and polar waters, providing food-rich currents that make the island a wonderful breeding ground for many fish-eating seabirds, despite the global fishing crash. Rising temperatures over the last century destroyed much of Iceland’s existing seabird population as part of the Sixth Extinction and, while other birds have replaced them, Atlantic puffins, arctic terns, and eighteen other iconic species are no longer found here.

Snæfellsnes, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Iceland’s Snæfellsnes peninsula once had scores of glacier-fed waterfalls such as this unnamed one during much of the last century. Luckily for today’s visitors, heavy rains often bring many of these beautiful waterfalls back to life.

Dettifoss, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

In the early twenty-first century when this photograph was taken, Dettifoss was the most powerful waterfall in Europe with flows up to 20,000 cubic feet of water per second. The substantial shrinkage of the Vatnajökull glacier, the primary source of the waterfall, makes Dettifoss now mostly a seasonal waterfall during the heavy spring rains.

Skagafjörður, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

This black sand beach on Iceland's northern coast no longer exists as rising seas have buried it under the surf. Iceland's coast suffered from dramatic changes resulting from the remarkable global sea level rise after the catastrophic collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Skagafjörður, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

While this sand beach no longer exists because of sea level rise, new black sand beaches have been created in Iceland resulting from the increased activity of the volcano Katla near Iceland's southern coast. When molten lava enters the cold ocean, the lava can cool so rapidly that it immediately creates debris and sand, and a sufficient lava flow can create a new black sand beach within a day.

Snæfellsjökull, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Glaciers such as Snæfellsjökull (which was declassified as a glacier in 2099) covered 11% of Iceland's surface area in 2018, but those glaciers that remain now only cover about 5% of the island country as they have shrunk dramatically or, in many cases, completely disappeared.

Skagafjörður, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

While volcanic activity helps to create new black sand beaches to replaces ones like this that are now buried beneath the sea, the number of miles of black sand beaches is now only 20% of what it was one hundred years ago.

Skagafjörður, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Warming oceans dramatically changed Iceland's fishery stock in the past century and a half, as warmer water fish such as flounder and mackerel slowly replaced traditional Icelandic catches of northern shrimp, herring, and scallop.

Sólheimajökull, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

The former Sólheimajökull glacial tongue left behind a beautiful deglaciated valley after retreating last century, and its proximity to Iceland's Ring Road made it the Icelandic government's choice for the location of its Icelandic Glacier Memorial Museum in 2101.

Sólheimajökull, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Skaftafellsjökull, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

As it melted, Skaftafellsjökull, like many glaciers, caused occasional but regular flooding as collapsing ice disturbed water underneath and its lagoon. The floods of this glacier (called Skaftárhlaup) often caused damage to nearby roads, but scientists usually had enough warning to prevent deaths of nearby residents. Flooding is no longer a problem for residents near Skaftafellsjökull after it melted away in the late 2070's.

Dettifoss, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Approximately 11 billion tons of Iceland’s glacial ice melted per year in the early twenty-first century, feeding spectacular waterfalls such as Dettifoss. As the glaciers melted the waterfalls actually increased in flow volume for a few decades until the flow dropped down dramatically, or disappeared entirely, as most of Iceland’s glaciers finally melted away.

Snæfellsjökull, Snæfellsjökull National Park, Iceland, 2018 (Copy)

Glaciers are not yet a fairy tale like the trolls and gnomes of Iceland's rich history of legends and lore, but scientists do not expect any of Iceland's few remaining glaciers to survive the twenty-second century because of the baked-in atmospheric warming, despite our current carbon neutrality. Glaciers and their history will likely always play a role in the identity of those who grow up in the landscape of this glacier-carved island.